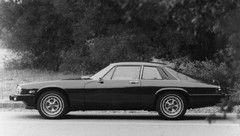

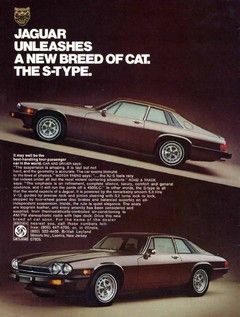

After the sublime E-type, the XJ-S was bit of a shock for the Jaguar faithful when it was launched in 1975, 30 years ago. The problem wasn’t so much the engineering – largely carried over from the successful XJ6 and XJ12 saloons. No, it was the styling.

For once, Sir William Lyons’ usually infallible sense of Jaguar style let him down. The XJ-S was an odd mixture of angles, slots and sweeping curves. The ‘buttresses’ at the back were an aerodynamic invention from Malcolm Sayer, who had shaped the D-type and much of the E-type, but from some angles they made the XJ-S look heavy and ill-proportioned. Long overhangs didn’t help, either, and the mixture of chrome (A-pillars, door handles) and modern matt-black (bumpers, window frames) just added to the confusion.

One observer reckoned the XJ-S had been styled by three people – who had never met…

XJ-S in US spec  US ad  1981 XJ-S V12 HE - a better car  Jaguar 3.6-litre XJ-S SC  Group 44 space-frame chassis  Tullius Group 44 car  1984 TWR Group A  1990 XJ-S convertible |

Looking beyond the styling, the XJ-S had plenty to offer. All four wheels were independently suspended, providing Jaguar’s usual top-class blend of road noise absorption, comfort and cornering poise. Under the bonnet sat Jaguar’s extraordinary 5.3-litre V12, the only V12 in volume production at the time and a paragon of smoothness and flexibility. The XJ-S could trundle happily in top gear at little more than walking pace, yet that same gear would take you all the way to 155mph – and practically in silence, too. That said, most of the cars sold were automatics, and that was where the problems started.

The auto itself, an established Borg-Warner job, wasn’t really to blame. The XJ-S was a big, heavy machine with a big, powerful engine and relatively unsophisticated fuel injection. Even with a manual gearbox, fuel consumption was not its strong point, and economy took a further nosedive when the self-changing ’box was fitted. As a result the XJ-S got a reputation as a heavy drinker. Motor magazine recorded 13.5mpg during its test: efficient German rivals like the BMW M635CSi and Porsche 928 were near enough as fast, the cheaper BMW delivering 17mpg and the pricier Porker over 18mpg.

And that wasn’t the end of the XJ-S’s woes. Jaguar was now part of the nationalised British Leyland Motor Corporation, and as Leyland management struggled to come to terms with the very real problems being faced by other companies in the group, Jaguar was allowed to slide.

Build quality suffered, reliability suffered, and by the early 1980s customers prepared to invest a still quite hefty sum in a Jaguar were dwindling. Waiting for a recovery truck on the hard shoulder of a motorway is bad enough, but at least with a Lamborghini you could sit and look at automotive art: with an XJ-S you just counted the wobbly panel gaps and paint runs.

In 1980, the Leyland board approved the beginning of the XJ40 project, which would eventually produce the next generation of Jaguar saloons. Alongside that, and sharing much of its platform and chassis engineering, came a sports coupé (XJ41) and drophead (XJ42) which were intended to do the job the XJ-S couldn’t. These two cars – the fabled ‘F-type’ Jaguars – would be lighter, quicker and more fuel efficient, and would be true successors to the E-type of the 1960s. The XJ-S was increasingly seen as an irrelevance.

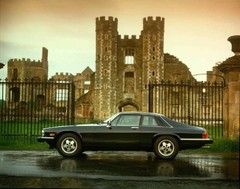

But the story wasn’t over yet. In 1981 Jaguar redeveloped the V12 engine using a new cylinder head design, incorporating the ‘Fireball’ combustion chamber design invented by Swiss engineer Michael May. The valves were now recessed into the head, with a circular pocket under the exhaust valve and a channel between the valves.

In the old V12, the pistons had carried combustion chamber bowls but they were now flat-topped, producing a higher compression ratio and a squish effect which created turbulence around the exhaust valve. The spark plug was resited to this side of the chamber, and the result was that the engine could now burn lean mixtures efficiently, cutting fuel consumption. The new V12, together with a higher final drive and some cosmetic improvements, went into a ‘High Efficiency’ (HE) XJ-S in 1981.

It proved to be the turning point. The revised XJ-S was a much improved machine, and it was now being better built by the men from Coventry. The XJ-S then received a further fillip with the introduction of a new body style – a cabriolet with a fixed roll-hoop, powered by a brand new engine, a 3.6-litre straight-six which would also be seen in the new XJ40 saloons. Despite worries about the engine’s lack of refinement (later fixed) the 3.6-litre XJ-S proved to be near enough as quick as the V12, without the fuel consumption penalty.

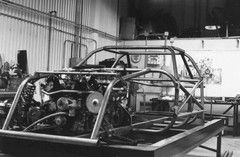

It was the V12, though, which was proving itself on the track. In the US, Bob Tullius’ Group 44 team ran a wild space-framed car (see pics above), while in the UK Tom Walkinshaw’s TWR team developed the big XJ-S into a successful Group A car for the European Touring Car Championship, Walkinshaw himself winning the title in 1984. That success would encourage Jaguar to bankroll a full Group C sports car programme, which would eventually net them a series of world championships and Le Mans wins.

The TWR team’s expertise hit the road in 1988 with the XJR-S, which was given a 318bhp 6.0-litre V12 engine in 1989, and uprated again to 332bhp in 1991. Meanwhile Jaguar introduced a full convertible (above), smoothed out the coupé’s looks and uprated both the mainstream V12 and the six-cylinder. And the XJ-S sold like never before.

By now Jaguar had been removed from the Leyland mess and privatised, and then in 1990 Ford had won a bidding war with GM to take control. Ford appointed Bill Hayden to run Jaguar, one of his first actions being to cancel the F-type – which was still nowhere near ready. Instead a new coupé, X100, was planned, together with massive investment in Jaguar’s production facilities to ensure that the new car could be built in a far more efficient way, and to much higher quality levels than before. That would become the XK8, with plenty of XJ-S engineering under its skin.

TWR’s XJ-S expertise would also be used to good effect by Aston Martin, another member of the Ford family, to produce the DB7 - the car that saved AM in the 1990s.

When the XJ-S finally finished its run in 1996, it had won many ardent admirers; not bad far a car which nearly died in ’79, unwanted and unloved.