Turning up the boost

Discussion

I have done a search and found nothing so sorry if it has allready been asked/discussed.

I know turbos use exhaust gasses to spin them up which blows compressed air into the engine.

I also know a simple remap is all it takes to give you more boost/power.

The bit i dont get is how electronics could possibly alter the amount of boost. Surely for more boost you would need more exhaust gasses to spin the turbo faster. So with that in mind to get more exhaust gasses you need more fuel burnt, which you wouldn't be able to do because the turbo wouldn't have spun up yet. Sooooo, what am i missing? How does the electronic signal give you more boost.

Thanks.

I know turbos use exhaust gasses to spin them up which blows compressed air into the engine.

I also know a simple remap is all it takes to give you more boost/power.

The bit i dont get is how electronics could possibly alter the amount of boost. Surely for more boost you would need more exhaust gasses to spin the turbo faster. So with that in mind to get more exhaust gasses you need more fuel burnt, which you wouldn't be able to do because the turbo wouldn't have spun up yet. Sooooo, what am i missing? How does the electronic signal give you more boost.

Thanks.

The most basic of systems uses a boost pressure sensor, and an electronically controlled boost controller.

Essentially, the more boost, the more voltage the pressure sensor produces. When a certain voltage is applied to the boost controller, it opens up the waste gate (through vacuum normally)which diverts the exhaust gases past the turbine, slowing it down. This limits the amount of boost that can be produced.

So the cheapest way to produce more boost, is by putting a resistor after the pressure sensor. It then thinks it's producing less boost at a certain point, and won't open up the wastegate until more boost is present.

I am not however, advocating that is the correct way to gain more boost.

Essentially, the more boost, the more voltage the pressure sensor produces. When a certain voltage is applied to the boost controller, it opens up the waste gate (through vacuum normally)which diverts the exhaust gases past the turbine, slowing it down. This limits the amount of boost that can be produced.

So the cheapest way to produce more boost, is by putting a resistor after the pressure sensor. It then thinks it's producing less boost at a certain point, and won't open up the wastegate until more boost is present.

I am not however, advocating that is the correct way to gain more boost.

A conventional exhaust driven turbocharger operates in what is known as a "positive gain" control loop.

Think of this situation:

1) running without boost, throttle is opened, more air (and more fuel) is burnt in engine, producing more exhaust gas

2) extra energy is removed from the exhaust gas by the turbine, and is added to the incoming air charge by the compressor

3) this extra air density allows you to add more fuel, and hence generate even more exhaust gas

4) loop returns to 2

Efectively, the system, if "uncontrolled" has a positive gain to infinity (in theory! In practise, things like choking and total efficinecy would limit the maximum boost possible

So, to control this system, a "wastegate" is used. This diverts exhaust gas around the turbine, so the energy escapes down the exhaust without being captured by the turbine. Effectively, opening this wastegate limits the gain of the system. An EMS system uses a pnuematic system to open the wastegate (usually against a metal spring holding it shut) The pnuematic system uses a solenoid valve (controlled by a PWM signal from the EMS) to either allow the wastegate to open, or to hold it shut to make more boost.

In a production car, there is an extra margin of control authority left in the boost control system, to account for wear, altitude, temperature, and component tollerance (effectively makes sure even the poorest system can make boost (and hence make the homologated power target)).

This extra margin is used by the "chippers" to extract more performance from a std engine at sea level.

Think of this situation:

1) running without boost, throttle is opened, more air (and more fuel) is burnt in engine, producing more exhaust gas

2) extra energy is removed from the exhaust gas by the turbine, and is added to the incoming air charge by the compressor

3) this extra air density allows you to add more fuel, and hence generate even more exhaust gas

4) loop returns to 2

Efectively, the system, if "uncontrolled" has a positive gain to infinity (in theory! In practise, things like choking and total efficinecy would limit the maximum boost possible

So, to control this system, a "wastegate" is used. This diverts exhaust gas around the turbine, so the energy escapes down the exhaust without being captured by the turbine. Effectively, opening this wastegate limits the gain of the system. An EMS system uses a pnuematic system to open the wastegate (usually against a metal spring holding it shut) The pnuematic system uses a solenoid valve (controlled by a PWM signal from the EMS) to either allow the wastegate to open, or to hold it shut to make more boost.

In a production car, there is an extra margin of control authority left in the boost control system, to account for wear, altitude, temperature, and component tollerance (effectively makes sure even the poorest system can make boost (and hence make the homologated power target)).

This extra margin is used by the "chippers" to extract more performance from a std engine at sea level.

Triple D said:

I thought waste gates just got rid of the back pressure that slows the turbo and puts strain on it.

Yep, but when an actuator gets weak it will allow the wastegate to lift off its seat, thus leaking boost. If the wastegate is fixed shut that can't happen.

I would venture a turbo with a jammed wastegate won't last long, lots of compressor stall = worn bearings, damaged blades etc.

We should add that a remap shouldn't just up the boost limit - more air means needing more fuel to prevent detonation. Most remaps will add more ignition advance too, which all helps to make a bigger bang , which means more exhaust gas, which will mean quicker spin up.. (at least thats the theory).

Edited by Crafty_ on Monday 9th April 20:10

A few other salient points:

1) Turbochargers do not "blow air into the engine". In fact, the reverse is true. A turbocharger simply acts to increase the density of the intake air charge, to a level that cannot be furnished by ambient atmospheric pressure alone. The actual pressure ratio across the engine is worse than for a normally aspirated engine. This is because a turbocharger is not (and cannot be) 100% efficient. Losses mean than it always takes more energy out of the exhaust than it supplies to the incoming air charge. This leads on to:

2) A turbocharged engine is always less efficient (given a like for like base) than a normally aspirated one, in terms of total fuel consumed verse power output. Ultimately the turbocharger takes some of the energy released during combustion, and uses it to boost the intake density. This means there is less energy availible to do useful work on the piston and hence a lower Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) compared to a N/A engine. However, the ability of the turbocharger to boost intake density (and hence mass flow) to levels far above that achieveable by atmospheric pressure alone, means that even though less efficient, the ultimate power output can be higher than for a similar capacity (geometric capacity) N/A engine.

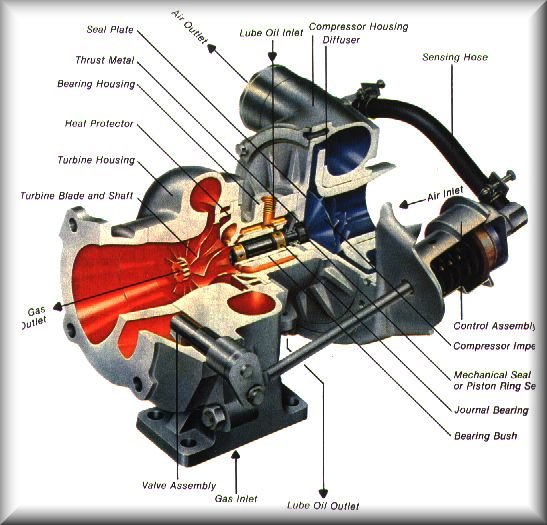

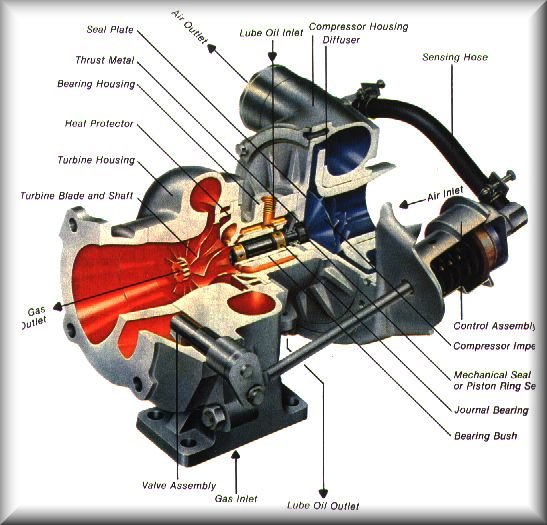

The picture below shows a "passively" controlled turbocharger (like the used to be in the 1980's)

The wastegate actuator takes a pressure feed (via the "sensing hose") from the compressor outlet. This pressure acts on a diaphram, and pushes on the actuator rod. The wastegate (labelled "valve assy" in that pic) is held shut by a fixed metal spring. As boost pressure increases, eventually the spring is overcome by the boost pressure force, and the actuator rod moves (to the left in that pic) opening the wastegate valve, and allowing some of the exhaust gas to bypass the turbine.

In an electronically controlled pnuematic system, the system can "block" or "vent" the pressure feed from the compressor allowing a higher boost pressure to be generated before the actuator is opened. In reality, the wastegate is also being pushed open by the pressure ratio across the turbine as well as boost pressure. Hence, for a conventional "spring closed, air pressure open" system, there is a limit to the maximum boost that can be made before the wastegate is blown open by the pre turbine exhaust pressure, even if no pressure has be allowed to reach the actuator diaphram by the control system.

1) Turbochargers do not "blow air into the engine". In fact, the reverse is true. A turbocharger simply acts to increase the density of the intake air charge, to a level that cannot be furnished by ambient atmospheric pressure alone. The actual pressure ratio across the engine is worse than for a normally aspirated engine. This is because a turbocharger is not (and cannot be) 100% efficient. Losses mean than it always takes more energy out of the exhaust than it supplies to the incoming air charge. This leads on to:

2) A turbocharged engine is always less efficient (given a like for like base) than a normally aspirated one, in terms of total fuel consumed verse power output. Ultimately the turbocharger takes some of the energy released during combustion, and uses it to boost the intake density. This means there is less energy availible to do useful work on the piston and hence a lower Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) compared to a N/A engine. However, the ability of the turbocharger to boost intake density (and hence mass flow) to levels far above that achieveable by atmospheric pressure alone, means that even though less efficient, the ultimate power output can be higher than for a similar capacity (geometric capacity) N/A engine.

The picture below shows a "passively" controlled turbocharger (like the used to be in the 1980's)

The wastegate actuator takes a pressure feed (via the "sensing hose") from the compressor outlet. This pressure acts on a diaphram, and pushes on the actuator rod. The wastegate (labelled "valve assy" in that pic) is held shut by a fixed metal spring. As boost pressure increases, eventually the spring is overcome by the boost pressure force, and the actuator rod moves (to the left in that pic) opening the wastegate valve, and allowing some of the exhaust gas to bypass the turbine.

In an electronically controlled pnuematic system, the system can "block" or "vent" the pressure feed from the compressor allowing a higher boost pressure to be generated before the actuator is opened. In reality, the wastegate is also being pushed open by the pressure ratio across the turbine as well as boost pressure. Hence, for a conventional "spring closed, air pressure open" system, there is a limit to the maximum boost that can be made before the wastegate is blown open by the pre turbine exhaust pressure, even if no pressure has be allowed to reach the actuator diaphram by the control system.

Edited by anonymous-user on Monday 9th April 20:33

Edited by anonymous-user on Monday 9th April 20:35

pretty good explanation Max Torque

If I can add my 2p's worth

It depends on the car, some have purely mechanical pressure related system, i.e. the actuator opens at a set boost pressure.

Others have electronic system and its these you can get chipped relatively easilly and they also probably sort out any 'mapping' adjustments as well.

The mechanical systems (e.g. 200sx for instance (if you ignore the lower boost in lower gears) you

- need something mechanical to bleed away the boost in a controlled fashion

- or something mechanical to hold the boost to a higher level before letting the actuator 'see it'

- or stronger/adjustable actuator

- or electronic control via a separate EBC

- or combinations of above

the above (certainly in the 200sx) can be handled reasonably well by the standard map and components up to a certain point. Mapping in a 200sx is a secondary consideration, it helps, but it has no real effect to the boost levels, just makes it run better at the higher boost. Once you start changing turbo's and injectors then you NEED it mapping.

I'm pretty sure ther are no longer any 'mechanical' controlled cars anymore most are from the 80's 90's maybe a bit into 00's

If I can add my 2p's worth

It depends on the car, some have purely mechanical pressure related system, i.e. the actuator opens at a set boost pressure.

Others have electronic system and its these you can get chipped relatively easilly and they also probably sort out any 'mapping' adjustments as well.

The mechanical systems (e.g. 200sx for instance (if you ignore the lower boost in lower gears) you

- need something mechanical to bleed away the boost in a controlled fashion

- or something mechanical to hold the boost to a higher level before letting the actuator 'see it'

- or stronger/adjustable actuator

- or electronic control via a separate EBC

- or combinations of above

the above (certainly in the 200sx) can be handled reasonably well by the standard map and components up to a certain point. Mapping in a 200sx is a secondary consideration, it helps, but it has no real effect to the boost levels, just makes it run better at the higher boost. Once you start changing turbo's and injectors then you NEED it mapping.

I'm pretty sure ther are no longer any 'mechanical' controlled cars anymore most are from the 80's 90's maybe a bit into 00's

Edited by sparkyhx on Monday 9th April 21:36

Gassing Station | General Gassing | Top of Page | What's New | My Stuff