PH Origins: Automatic transmissions

How simplicity, safety and non-synchromesh manual gearboxes gave rise to the fully automatic transmission

If you were to sling a modern driver into an early automobile, they'd probably struggle to start the thing, let alone make any meaningful progress down the road. Such cars, with their odd pedal layouts, wheel-mounted throttles, heavy clutches, manual advance control and often unforgiving ride, would make smooth and steady forward motion a challenge for those inexperienced in operating them.

Many would also find it difficult to deal with the unsynchronised transmissions of the era, which would require precise throttle and clutch control to avoid jarring, grating shifts. Slip up momentarily on a hill and you could quite easily find yourself with a box full of neutrals, stamping on the pedals and waving the gear stick in terror, as you merrily started coasting backwards into similarly panicking motorists.

Besides requiring skill and care, this posed a plethora of problems for the less practised motorist. The first was the ease with which a driver could lose control; then there was the fact that the attention required to execute slick gear changes could distract from the process of safely getting down the road. Those travelling longer distances over rougher terrain could also tire quickly, again giving manufacturers safety-related cause for concern.

The answer was obvious: do away with the clutch and somehow automate the process of changing gears, so the driver could relax and pay full attention to the road ahead. Fortunately, in the early 1900s, technology was forging ahead - particularly in the areas of industrial and electronic control systems and automation.

During 1883, the Sturtevant Mill Company had been founded in America. It quickly established itself as the manufacturer of advanced materials handling and processing equipment and, as younger family members joined the business, it began using its expertise to branch out into new areas.

Thomas J. Sturtevant, who had graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and joined the company in the late 1800s, saw the potential of the new automotive market. He subsequently set about designing hardware that would help Sturtevant secure a foothold in this burgeoning business, ranging from carburettors through to complete engines. Having then discovered how problematic the process of getting drive from the engine to the wheel was proving, he began to tackle the issue of power transmission.

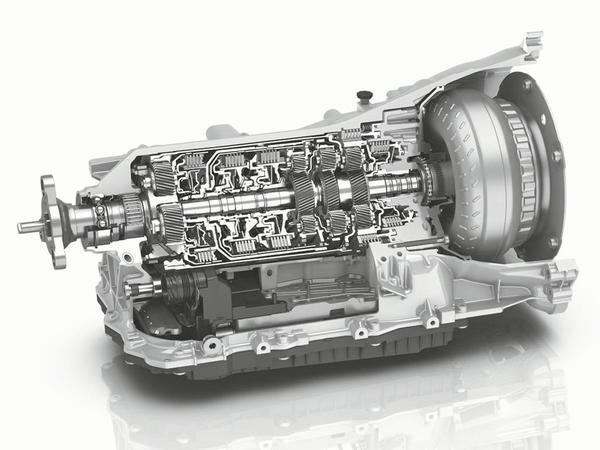

Sturtevant subsequently designed and patented, in 1904, a two-speed automatic transmission. It was based on independently operating, centrifugally controlled multiple-disk clutches that ran in an oil bath to prevent excess wear and tear. As the engine accelerated, weights controlling the clutches would be flung outwards at predetermined points to engage the friction material with hubs connected to the output shaft; when engine speed rose further, the first clutch would be disengaged and the second would step in - and drive through a different set of gears via its own hub. Sturtevant envisioned it getting more complicated, too, stating 'Additional clutch devices and gearing connections may be employed for... three or more undetermined speeds of rotation.'

This gearbox, along with the company's own engine and brakes, went into a car called the Sturtevant Automatic Automobile in 1905. Alas, it was not to prove a success. The transmission was simply too complicated, and the materials required not yet available, resulting in the centrifugal clutches frequently disintegrating and destroying the transmission.

Several similar efforts followed but, once again, none proved commercially viable. It took until 1933 for another run to be taken at lightening the driver's workload, with the launch of the REO Motor Car Company's 'Self-Shifter'. This semi-automatic arrangement featured a centrifugally operated two-speed automatic, like Sturtevant's, which effectively reduced the driver's input to just controlling a clutch when moving off or coming to a stop. '33 1/3% easier to drive... your hands free for the wheel!' claimed REO's marketing materials proudly.

This approach was echoed by the semi-automatic 'Automatic Safety Transmission', used by Buick and Oldsmobile, which arrived in 1937. It had a conventional clutch arrangement for starting and stopping, or shifting into reverse, but changes were otherwise automatic. This was achieved by a centrifugal governor that controlled hydraulic pistons, which would shift brake bands and clutches within the four-speed gearbox's pair of planetary gear sets.

Using one of these transmissions was less complicated than the likes of the Wilson pre-selector found in Daimler's touring cars, which required drivers to select the desired gear then cycle the transmission with the gear-change pedal. Many of these pre-selector gearboxes, however, had done away with a driver-controlled clutch between the engine and transmission. Instead, they used a fluid coupling that could transmit drive smoothly between its driving and output turbine.

Chrysler introduced a similar semi-automatic arrangement in 1939, called the 'Fluid Drive', which featured a three-speed manual equipped with a fluid coupling and a clutch; the latter only had to be used briefly when engaging first or changing, otherwise the fluid coupling would deal with the smooth transmission of power - regardless of which gear you were in. You could put it in third and simply drive around all day if acceleration wasn't on your list of priorities.

However, since its inception in 1920, the new General Motors Research Corporation had been busying itself with the task of finding a new, straightforward transmission that would do away with the grief of dealing with manual shifting and clutch actuation. All manner of ideas had been explored, ranging from combustion engines coupled to generators that powered electric motors, through to continuously variable transmissions - which were of great interest to GM, although later sidelined due to material problems.

Much time had also been spent exploring the concept of fluid drives and hydraulically shifted transmissions. Given the issues experienced with CVT development, the development team returned to exploring these seemingly more viable types of gearbox in the middle of the 1930s.

At this point, though, with fluid couplings becoming increasingly prominent and available, GM's engineers now had a way around the problem of the clutch pedal: combining the fluid coupling with the company's hydraulically shifted planetary gear and clutch units. Some state this innovation came from a Brazilian engineer called Jose Braz Araripe, who developed a hydraulically operated transmission that was reputedly sold to GM, but no formal reference to this exists.

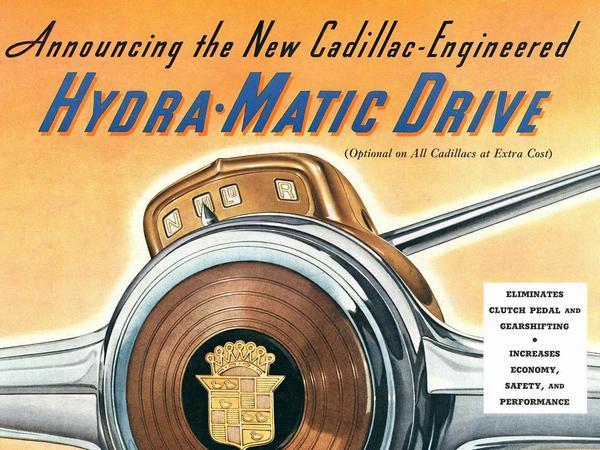

In any case, by 1939, GM's engineers had developed a production-ready, fully automatic transmission called the Hydra-Matic. This combined the fluid coupling with a hydraulically shifted gearbox, the basis for which came from the Buick and Oldsmobile Automatic Safety Transmission. The result was a four-speed automatic that was described as 'simplicity itself'. It was ultimately announced in October 1939 and was offered by Oldsmobile in 1940, before Cadillac rolled it out in 1941.

The Hydra-Matic design quickly found use in heavy-duty applications, too, as it proved ideal for America's tanks in World War II. They lessened the load on the driver, making it easier for them to keep good control of the tank, and they helped avoid inadvertent stalls. A static tank was, after all, particularly easy to hit - so keeping them moving, particularly when under duress, was of great importance.

'Stands up... in the fiercest battle action! In the toughest wartime driving!', proclaimed GM's advertising material. Suffice it to say that little more was needed to convince the general public of the reliability of the new transmission, while the ease of use was evident from the first time a potential buyer drove a Hydra-Matic car off the lot.

Just prior to the war, GM had also begun developing another fluid coupling that would further improve the performance and behaviour of its automatic transmission. It featured a special bladed assembly, called a stator, which altered the fluid flow between the two halves of the coupling and allowed for torque multiplication - resulting in a 'torque converter' that granted far smoother and stronger off-the-line performance.

This was a development of similar converters that had already been conceived overseas. Swedish engineer Alf Lysholm, for example, had developed several concepts including an efficient multi-stage unit. Similarly, German engineer Hermann Rieseler had proposed a converter featuring adjustable blades for obtaining 'practically serviceable efficiencies' in 1922.

Redesigned GM transmissions equipped with a torque converter were soon made available, in 1948 as the Buick 'Dynaflow' and 1950 as the Chevrolet 'Powerglide'. Europe wasn't far behind in the automatic race, either; Borg-Warner introduced its 'Ford-O-Matic' three-speed automatic in 1950. Though it took ZF, which would later become well regarded for its eight-speed automatics, until 1965 to release its first passenger car automatic.

Back in the US, the more advanced automatics proved an astonishing success, ultimately being the transmission of choice in almost all of GM's individual brands. It remains the case, on a wider scale, even in the modern era; according to a story published in the LA Times, featuring contributions from US automotive specialist Edmunds, fewer than 3% of the new cars sold in American in 2016 featured a manual transmission.

Given the increasing traffic on the road, changes in motoring habits and interests - and the easy integration of advanced driving aids with automatic gearboxes - the decline of the manual transmission is surely set to continue.

Gassing Station | General Gassing | Top of Page | What's New | My Stuff